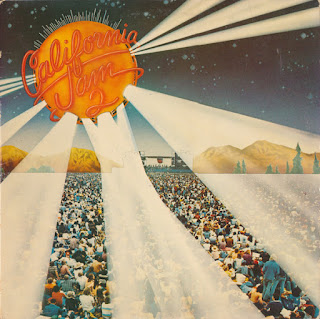

April 6, 1974 Ontario Motor Speedway, Ontario, CA: Emerson Lake & Palmer/Deep Purple/Black Sabbath/Black Oak Arkansas/Seals & Crofts/Eagles/Earth Wind & Fire/Rare Earth (Saturday) California Jam

The Ontario Motor Speedway in Ontario, CA, 35 miles East of Los Angeles, is largely forgotten today, as was the major rock concert held at the Speedway on April 6, 1974. Yet the "California Jam," as it was called, had great economic significance in the history of rock concerts, in that it had the highest paid attendance of any rock concert up until that time. The paid attendance record was only known to have been eclipsed one time--at the successor concert at Ontario Speedway on March 18, 1978, known as "California Jam II". The 168,000 paid attendance--out of probably 200,000 in total--at the 1974 show make it an important event, yet rock history has put it aside. This post will look at the 1974 California Jam concert at Ontario Motor Speedway in its proper context, and reflect on how it was both influential, profitable and yet repeated only a single time.

Rock Festivals and Major Rock Venues: Status Report, Early 1974

Rock Festivals were a product of the 1960s. Gina Arnold's excellent book Half A Million Strong (2018 U of Iowa Press) tracks how "free shows in the park" evolved into "giant multi-day events in some farmer's muddy field" over the course of a few years (yes, she's my sister, but you should read it). By the time of the biggest festivals of 1969 and 1970, most famously Woodstock, hundreds of thousands of people would come to some outlying area and camp out for several days, while live rock music blasted 24/7. Legendary as these events were, most fans did not attend more than one giant event, and most communities that had endured a huge rock festival did not tolerate a second one.

Live rock music got bigger every year, and various efforts were tried to find a way to have "festival" events on a large scale. Multi-act events were appealing to promoters because they inherently hedged risk in a volatile music market. Since shows had to be planned many months in advance, and it was hard to anticipate how one band might have a breakout hit, and how another may have become over the hill, or even broken up, in the few short months between booking the show and playing it. In early 1969, for example, Led Zeppelin found themselves playing tiny auditoriums, sometimes as the opening act, with their debut album roaring up the charts, while Vanilla Fudge found themselves no longer the draw they had been the year before. A rock festival, with dozens of acts over a few days, could more easily absorb the hits and misses. Promoters continued to search for a way to book multiple acts profitably.

Rock Concerts at Auto Racing Tracks

The immediate and vast popularity of rock festivals posed a very specific land-use problem. Places like Indian Reservations and farms were not really viable for major, multi-day events, since too many things could go wrong. Equally importantly, despite or because of the increasing crowds, it was all but inevitable that rock festivals would become "free concerts." Liberating as this may have seemed at the time, it ensured that the events could not make enough money to provide a safe, repeatable event for bands, patrons and host communities. The financial opportunities of rock festivals were huge, however, and since nothing says "rock and roll" like "land use," over the years there was a concerted effort in the concert industry to find spaces that could successfully and profitably host occasional, loud outdoor events with giant crowds.

One of the intriguing solutions for hosting giant rock festivals was to use facilities designed for auto racing. Race tracks were usually somewhat removed from urban areas while still being near enough to civilization to attract a crowd. Auto races themselves were noisy, and major race events tended to occur just a few times a year and last an entire weekend, just like a rock festival. Since race tracks were permanent facilities, they generally had fences, bathrooms, water, power and parking, so in many ways they would seem like ideal venues for huge rock events. Indeed, some of the major rock events of the 1969 and the 1970s were held at race tracks.

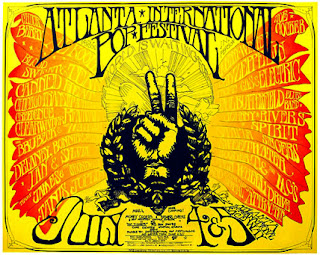

Two of the most successful rock festivals were held at Texas Speedway and Atlanta Speedway, both organized in 1969 by promoter Alex Cooley. Both Speedways were NASCAR ovals. The Rolling Stones' debacle at tiny Altamont Speedway might have had a very different outcome had it been held at its original site, the newly-opened Sonoma Raceway, a Road Racing course in rural Sonoma County, near the San Francisco Bay.

I looked at some of the history and economic dynamics of Auto Racing tracks as Rock Concert sites in another post, although for purposes of scale I focused on the Grateful Dead. Generally speaking, while auto racing had been popular since the invention of the automobile, horse racing had been hugely popular in cities and county fairs throughout the United States long before cars were invented. However, after WW2, when the GIs returned and economy boomed, America moved from its rural roots to a more urban and suburban universe, and the automobile became a more important part of everyone's life. A national boom in the popularity of auto racing corresponded with a slow decline in the popularity of horse racing.

By the early 1960s, numerous custom-built facilities served the thriving auto racing industry, with oval tracks (for NASCAR and "Indianapolis" cars in the South and Midwest), road courses (for sports cars on both coasts) and dragstrips (nationwide). These facilities were ready made for rock concerts, but there were some huge cultural divides. With a middle-class family audience for auto races, with their Dow Industrials sponsorship from major companies, racetrack promoters were neither tuned in to nor inclined towards sponsoring long-haired outlaw rock concert events flaunting nudity and drugs.

The most important 1970s rock concert event at an auto racing track was the infamous "Summer Jam" at the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Racecourse, on July 28, 1973. Officially, it was just a single day event with only three groups: the Allman Brothers Band, the Grateful Dead and The Band. Watkins Glen was in upstate New York, 250 miles Northwest of Manhattan, and 200 miles West of Woodstock. Watkins Glen Racecourse was the site of the annual Formula 1 United States Grand Prix, and huge crowds in the 50-100,000 range convened there annually for Grand Prix weekend. It seemed like a perfect spot for a rock festival.

Of course, although many tickets were sold, apparently as many as 150,000 (at $10 per), 600,000 or more fans actually showed up and the concert rapidly became free. The Dead played a set at soundcheck the day before (July 27), as did the other bands. In the end, the weather was good, nothing went wrong, a good time was had by all, the promoters seem to have made money and no one wanted to do it again. With that many people, something was eventually going to go wrong. Ironically, if the Dead had played Watkins Glen with less dramatic support (just the New Riders and The Sons, for example), maybe only 50,000 would have showed up, and it would have become an annual event. But any willingness to support this sort of event in the heavily populated Northeast disappeared forever at midnight as members of all three bands rocked through "Not Fade Away" and "Mountain Jam" for half a million fans as they closed the concert.

The California Jam, at Ontario Motor Speedway, would follow the next Summer, with a very different configuration. It's another forgotten fact, however, that both the Dead and the Allman Brothers were booked at Ontario Motor Speedway on May 27, 1973, just two months before Watkins Glen. The largest rock concert in American history nearly had a preview, between Los Angeles and San Bernardino.

May 27, 1973 Ontario Motor Speedway, Ontario, CA: Grateful Dead/Allman Brothers Band/Waylon Jennings/Jerry Jeff Walker (Sunday) Bill Graham Presents-CanceledI recently discussed the history of the concert scheduled for Sunday, May 27, 1973, featuring the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers and Waylon Jennings. The concert was booked and advertised, but ultimately it was canceled with a week to go. The stated reason was that the local police wanted the show to end by nightfall, but it's more likely that ticket sales were insufficient. If Bill Graham had sold 150,000 tickets, as he had hoped, he would have found a way to assuage any concerns--if they were real at all--about performing at night, with extra lights, added security or whatever it took. I think that the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead, while both popular bands, were not a destination concert for 1973 Southern California fans. Old San Francisco or Georgia hippie stuff just wasn't ringing bells in Los Angeles, and every high school student for 100 miles around wasn't going to drive to Ontario for that. So the concert was canceled.

There were some other subplots at play this weekend. May 27 '73 was the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, which was the day of the Indianapolis 500. The Ontario Motor Speedway was not going to try and draw racing fans during the biggest televised auto racing event of the year, so they would have been ripe for another event. After the grand opening of the Speedway in August 1970 (discussed in more detail below), the Speedway had under-performed. Bill Graham, meanwhile, although the King of the San Francisco concert scene, had only occasionally put on shows in LA. There was no dominant promoter in Southern California, so it was just like Graham to identify a new and willing partner and introduce himself with a huge bang. Prudence won out, however, and the '73 Dead/Allman show at Ontario was canceled. Yet the same pair, plus The Band, were the attractions at the largest rock concert in American history just 2 months later at Watkins Glen. So Graham was onto something, but he was off by 2 months and 3000 miles. It turns out, he was also right about Ontario Motor Speedway, but that would take another year.

update 20240201: it turns out a Leon Russell concert was indeed held at Ontario Motor Speedway, on Sunday, July 29, 1973. This was the first rock concert at the Speedway. Leon had just released his monster hit triple album Leon Live. Per the July 31 Times, around 30,000 showed up, but Bill Graham was expecting 80,000. In a strange bit of symmetry, this was the same weekend as the Dead/Allmans blowout at the Glen, and Leon had originally been booked there. The Dead and the Allmans had preferred The Band, and Leon was bought out of the gig.

November 24, 1973 Ontario Motor Speedway, Ontario, CA: Three Dog Night/Guess Who/Chuck Berry/Canned Heat/Blues Image/Azteca/Mag Wheel & The Lugnuts/Tower of Power (Saturday) November Jam

Between the canceled Dead/Allmans show in May '73, [and the July Leon Russell show] and the epic California Jam in April of 1974, there was one other event, utterly forgotten. The "November Jam," on Saturday, November 24 was attended by less than 50,000. It never rains in Southern California, as we know, except when Three Dog Night was your headliner. LA Times rock critic Dennis Hunt reviewed the grim proceedings on Monday (November 26):

A Cold Concert In Ontario (Dawn To Dusk Rock)

A cold, windy drizzly day is lethal to a marathon outdoor rock concert. Hours of exposure to bad weather is no fun. Unfortunately, it was damp and chilly on Saturday at Ontario Motor Speedway. The dawn to dusk concert there was not as enjoyable or well attended as it might have been on a warm, sunny day.

Under the circumstances, the crowd was fairly large. The security guards estimated that between 10-15,000 were present when the gates opened at 6:15 am and that, by afternoon, there were between 20-25,000....I arrived in the afternoon and endured a long, awful set by Three Dog Night and part of the Guess Who set. Chuck Berry was scheduled to close the show, but late in the afternoon the announcer reported that he had never arrived. When the Guess Who appeared, it was dark and drizzling steadily. Most of the crowed left after the Three Dog Night. Many who stayed to see the Guess Who perform departed after the first few numbers since it was evident that the group, understandably, was not in good form.

While this show was forgettably bad, and not much fun, it does mean that a successful rock concert was held at the Ontario Motor Speedway. Some lessons must have been learned, whatever they were, and a bigger event with major acts, at a more favorable time of year, must have seemed viable. Remember, April in Los Angeles is generally beautiful, and it really doesn't rain in LA in the Spring. So a big Spring rock festival type event at Ontario Speedway must have seemed very plausible indeed.

The Ontario Motor Speedway was an innovative and newly

constructed auto racing track that had only opened for full-time racing

in Summer 1970. Ontario, CA, had been founded in 1891, named by

transplanted Canadians. Ontario is 35 miles East of Los Angeles, and 23

miles South of San Bernardino. Part of San Bernardino County, it is on

the Western Edge of the so-called Inland Empire. Ontario had been the

site of a World War 2 Army Air Force Base, which remained an Air

National Guard base (and would remain so through 1995). The airport had

also been established for civilian use in 1946 as Ontario International

Airport. The Airport was joined to LAX in 1967, and jet flights had

begun at the airport in 1968. Although Ontario only had a population of

64,118 in the 1970 census, as a result of the airport and the airbase it

was at the nexus of a substantial freeway network. I-10 and I-15 met at

Ontario Airport, so all of Southern California could get there easily.

Auto racing was booming in the 1960s, and Los Angeles was under-served by facilities. Yes, there was the epic Riverside Raceway, another 25 miles East, but that made it even farther from LA proper. More importantly, Riverside was just a road racing facility--albeit a great one--and that limited the types of major events that could be held there. Ontario Motor Speedway was conceived as a full-service answer to every auto racing sector in the Los Angeles area, in a location even nearer to the city. The airport location was crucial, too, since major auto racing teams barnstormed around the country like touring rock bands, and drivers and even their race cars were always flying directly from track to track.

Ontario Motor Speedway was custom built to provide first class facilities for all the major types of racing: an oval for NASCAR and Indianapolis cars, a road course (that included part of the oval) for road racing and a dragstrip. Besides advanced pit facilities, OMS also pioneered what we now call "clubhouses" and "luxury suites" for sponsors. It was a well thought-out endeavor. The plan was to have not only top level NASCAR and USAC (Indy Car) 500-mile races, but Formula 1 and NHRA Drag racing. The inaugural race was the (Indy Car) California 500 on September 6, 1970, with paid attendance of 178,000, a huge crowd even by auto racing standards. Jim McElreath beat out an All-Star field of drivers that included Mario Andretti, A. J. Foyt, Dan Gurney and the Unser brothers.

After a hugely successful opening, however, Ontario Motor Speedway had a number of events in 1971 and '72 that did not live up to financial expectations. The racing was great--it was the early 70s--but after the September '70 opening, the Speedway didn't catch LA like it should. The big plan was that Ontario would host a 2nd United States Grand Prix, which hitherto had been the exclusive province of Watkins Glen in New York. As a prelude, Ontario Motor Speedway held a non-Championship Formula 1 race, the Questor Grand Prix, on March 28, 1971, won by Mario Andretti in a Ferrari 312B. The event was a financial bust, however, and Formula 1 cars never ran at Ontario again (ultimately Long Beach, CA, would get the second US, Grand Prix). Although 1971 went alright, the 1972 Ontario attendance--despite great racing--were a financial letdown. Thus by 1973, Ontario Motor Speedway would have been open to the possibility of different promotions.

Southern California Stadiums

There

were plenty of stadiums in Southern California, but none of them were

particularly ripe for rock concert promoters. Dodger Stadium was under

the full control of the Dodgers, and they didn't share it. Anyway, it was baseball season. The Los

Angeles Coliseum was old (opened 1921) and in and "undesirable" (read:

"too African-American") neighborhood. The Rose Bowl, in Pasadena, had

access and parking issues. That left Anaheim Stadium, in Orange County.

But it was just across the road from Disneyland, and The Mouse would not

want weekend parking disrupted by hordes of young rock fans. In the end,

starting around 1976, Anaheim Stadium would become the primary home of

stadium rock concerts in Southern California, with the full cooperation

of Disneyland, but that was a few years away.

Ontario Motor Speedway was a different matter. It had been well-conceived and well-financed, but after initial excitement attention had died down--same as it ever was for LA--it was going to need additional sources of revenue.

What did the Ontario Motor Speedway offer as a rock concert venue?- Its location (35 miles E of LA, 23 miles Southwest of San Bernardino) put it in close proximity to tens of thousands of potential rock fans

- The convergence of the I-10 and I-15 freeways meant that an even larger pool of rock fans could drive to the Speedway fairly easily, from either San Diego (on I-15) or nearer the Pacific Coast (I-10). Ontario was just outside of Central LA, so the majority of potential fans could circumnavigate the often brutal traffic jams that the region was infamous for.

- In Southern California, it's always sunny and it never rains, so weather wasn't a consideration.

- The

racing facility had parking for 50,000 cars, and apparently there were

satellite lots as well. No need to worry about cars abandoned by the

side of the road on some farm road (although that would turn out just the same as at Woodstock, even if it didn't initially seem so)

- The grandstands featured 95,000 seats, with 40,000 "bleacher" seats in temporary grandstands, and a substantial crowd could fit on the infield. It was plausible to imagine 200,000 or more fans at a rock concert (178,000 had attended the inaugural California 500 race). This was double the capacity of even the enormous LA Coliseum.

- Ontario Motor Speedway had debt to service and was looking for other sources of revenue, so they would be eager to work with any well-financed partners

- Most importantly,

the huge grandstands around the track, and hence around the whole facility,

ensured that the facility was cordoned off. That meant it was plausible

to ensure that only those with tickets would get into the show. At giant

rock festivals, the economic issue was always gate-crashing, but that

was usually in some giant, muddy field. The Speedway itself acted as fence, and

entry was through controlled tunnels under the grandstands. Gary Stromberg, a publicist for Bill Graham, had commented on this the previous year (LA Times May 5 '73), saying "the Speedway has high fences and special tunnel

entrances that were built specifically to deter would-be gate-crashers." So this was no afterthought.

In November 1972, ABC quietly began a revolution in late night television when it broadcast two 90-minute In Concert shows. The first one (November 24) had featured Alice Cooper, Curtis Mayfield, Bo Diddley and Seals & Crofts, while the second (December 8) had showcased the Allman Brothers (with bassist Berry Oakley's last performance), Blood, Sweat & Tears, Chuck Berry and Poco. All the acts had been filmed live at Hofstra University on November 2, 1972, rather than in a sterile TV studio.

ABC In Concert had gotten tremendous ratings, and ABC had made it a regular bi-weekly show. NBC had followed with the Midnight Special, and that in turn was followed by the syndicated Don Kirshner's Rock Concert. So for young teenagers like myself, the weekend was full of actual rock bands playing actual live rock and roll, sometimes simulcast on FM radio. It was our first opportunity to see what some of these bands looked like on stage. Not only were the shows successful in their own right, but they helped teach networks that there was a TV audience for late at night, particularly for young people. Shows like Tom Snyder's Tomorrow, Saturday Night Live and Fernwood 2Nite would soon come.

The California Jam concert was produced by veteran promoters Sandy Feldman and Leonard Stogel. The bands were booked by Pacific Presentations, a Los Angeles-based agency with a national profile, who worked with just about every touring act in the country ABC had made the decision, however, to videotape all of the California Jam, and broadcast highlights of it in four shows between May 24 and June 21. For one thing, the TV broadcast made the band's appearances even more high profile. I do not know the financial terms of the broadcast, but ABC helped underwrite Cal Jam in some way, adding to the financial stability of the event.

California Jam: The Bands

The California Jam show was only a single day of performances, but it was scheduled to go for about twelve hours. There were eight performers. All of the bands were popular, but none of them were a singular attraction that was going to provided the bulk of the drawing power. It's important to remember that the rock audience was still pretty young at the time. Someone who had first heard the Beatles in 1964 at, say, age 11, would only have been 22 by 1974. Much of the audience would have been even younger than that. People in High School or College tend to travel in packs. The goal for the Cal Jam booking was to provide something for a wide spectrum of young white Southern California rock fans. That meant that for a carful of teenagers, everyone had something they were looking forward to.

|

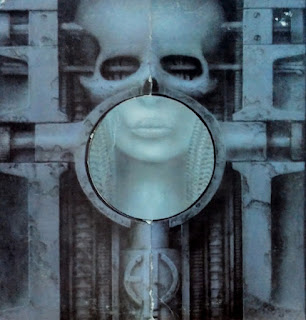

| Brain Salad Surgery, ELP's 5th album (first on Manticore/Atlantic) released in January 1974 |

Emerson, Lake and Palmer were the headliners, booked to close the show after nightfall. They had just released their fifth album Brain Salad Surgery, in January. After the trio's previous album, Trilogy (on Island) had reached #5, ELP (as they were known) had signed with Atlantic. Atlantic had given them their own "Imprint" label, Manticore Records. Brain Salad Surgery would reach #11. ELP were dramatic live performers, playing surprisingly difficult music in an energetic way. Back in 1970, they had had a modest hit single with "Lucky Man," but they were an album band, famous for Keith Emerson's prodigious keyboard skills and Carl Palmer's powerhouse drumming.

ELP had formed out of the ashes of Emerson's 60s trio, The Nice. The Nice were progressive rock pioneers, featuring Emerson's formidable organ and piano skills, augmented by odd time signatures and orchestral accompaniment. Along with the difficult stuff, The Nice would do highly musical covers of Bob Dylan songs and the like. They were very popular in England. The Nice had ground to a halt by the end of 1969, and Emerson and Greg Lake teamed up, finding Palmer in early 1970. Almost from their inception, the band's merger of classically-themed pieces and loud rock virtuosity made them a huge concert attraction. ELP was the first really successful Progressive rock band, and they were a huge concert draw. ELP showed that rowdy young men could get just as excited about a 20-minute rock adaptation of a classical theme as they would for a blues boogie.

|

| Deep Purple's Burn, released February 1974. The first album by Deep Purple Mk. III |

Deep Purple had been around since the 1960s, but had only skyrocketed to popularity with the live album Made In Japan. Made In Japan had been released in April 1973, even though it had been recorded prior to the release of the studio album Who Do We Think We Are?, which had been released in January of 1973. Thanks to the live album, EMI released the two-year old "Smoke On The Water" (from 1972's Machine Head) as a single in May, 1973. It would reach #2 and became Deep Purple's signature song. Deep Purple straddled the line between hard rock and somewhat more serious music. EMI had given Deep Purple their own imprint, Purple Records, just as Atco had done with ELP.

Machine Head ('72), "Smoke On The Water," Made In Japan and Who Do We Think We Are? were all produced by the "classic" Deep Purple lineup (now known colloquially as Deep Purple Mk 2), which had been together since late 1969:

Ian Gillan-vocals

Ritchie Blackmore-lead guitar

Jon Lord-organ, keyboards

Roger Glover-bass

Ian Paice-drums

By the time of Cal Jam, however, Gillan and Glover had left Deep Purple. They had been replaced by lead singer David Coverdale and bassist/vocalist Glenn Hughes (ex-Trapeze). The new lineup (known informally as Mk 3) had just released Burn in February '74. Burn was a big success, and would reach #9 on the Billboard album charts.

The members of ELP and Deep Purple had been slogging around the English rock scene in the '60s, playing in a variety of good and bad bands, some known and some obscure. Now here they were, after nearly a decade, at the top of the bill at a giant venue in Southern California, with their new albums racing up the charts.

The Eagles had just released On The Border, their third album for Asylum Records in March 1974. The album would ultimately reach #17 on the Billboard charts and sell two million copies (double platinum). The record would have three huge, memorable singles: "Already Gone" (released April 19 '74), "James Dean" and "Best Of My Love." The Eagles were already really big, but they were going to get much, much bigger. The Eagles rocked a little bit, but they were much mellower than ELP or Deep Purple. When you realize that the booking concept of Cal Jam was to bring carloads of teenagers, you can see how while ELP or Purple appealed to many young men, the Eagles and Seals & Crofts were going to be more interesting to their girlfriends.

The Eagles had recently expanded to a quintet, with guitarist Don Felder joining the band. While the Eagles were on tour (it had started on March 26) Felder's wife was having a baby. The Eagles were not going to cancel a high profile concert, planned for TV broadcast, but they weren't apparently comfortable playing in front of a huge crowd in quartet format. Thus they drafted Glenn Frey's former housemate, one Jackson Browne, to be a "guest member" for California Jam. Browne played piano and guitar, and sang along on "Take It Easy" and some other numbers.

Black Sabbath of course had no radio hits, nor much in the way of FM airplay. Nonetheless they were hugely popular. In December, 1973, they had released their fifth album Sabbath Bloody Sabbath. Released on Warner Brothers in the US (Vertigo in the UK), it would reach #11 on Billboard. Black Sabbath's lineup was still the original, classic lineup with Tony Iommi on guitar, Geezer Butler on bass, Bill Ward on drums and of course Ozzy Osbourne on lead vocals.

Black Oak Arkansas, a Southern boogie quintet that really was from Black Oak, AK, had just released their fifth album on Atco, High On The Hog. The album would be the high water mark for the band, reaching #52 on Billboard. The album included the single "Jim Dandy," which itself went to #55. Black Oak Arkansas were amongst the initial wave of Southern rockers, even though they sounded quite a bit different than the somewhat jazz-and-R&B influenced Allman Brothers. Black Oak Arkansas' twin guitar attack was pretty much straight boogie. It's actually harder to play high-speed shuffles than it appears, so the band may have been better than they were given credit for, but they did not have the reputation for musical virtousity like the Allmans and their peers. Black Oak was another band that were popular with rowdy young men, like Deep Purple and Black Sabbath.

Dash Seals and Jim Crofts were both long-time professional

musicians from Texas. Both of them had been in The Champs, albeit

touring some time after "Tequila" had been a smash hit in 1958. Both of

them had also backed Glenn Campbell in Van Nuys nightclub, back in the

early 60s, when Campbell was an established session musician but not yet

a recording star. After various ins and outs, they ended up as a

singer/songwriter duo signed to TA Records. Seals and Crofts self-titled

debut came out in 1969, and their follow-up Down Home would come

out in September 1970. They would not see big success until after they

signed with Warner Brothers in 1971. By '72, they had huge hits with

"Hummingbird" and "Summer Breeze," and the Summer Breeze album from September was equally giant. "Diamond Girl," from April 1973, was equally huge. The album would reach #4, and the title single would release #6.

Seals & Crofts' newest album was Unborn Child. It had been released in February 1974. Warner Brothers had warned the duo that the subject of abortion in the title track was not going to be commercially popular, and they were correct. The album would only reach #18 on Billboard, with no hit singles, and the duo's popularity crested after this album. On stage, the pair were usually backed by a small combo. Once again, it's clear that Seals & Crofts filled out the bill to provide some contrast to the many loud, hard-rocking acts on the show. While the pair sometimes performed just as a duo, at Cal Jam they were supported by a full band, with drums, bass and percussion.

Earth, Wind & Fire are soul legends to this day, and rightly so. Yet it may seem strange that they appeared at one of the biggest rock festival events of all time, seventh on the bill below loud, long-haired bands like ELP, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath. There are two main point to reflect upon.

Firstly, while Earth, Wind & Fire was already extremely popular, their sound in 1974 was pretty different than when they would become absolutely huge a few years later. Founder Maurice White had been a jazz and studio drummer in the 1960s, playing with the Ramsey Lewis Trio, among others. When he founded Earth, Wind & Fire, while there was a healthy serving of soul and dance music, there was a lot of jazz and funk, too, with a nice overlay of African sounds ("World Music" wasn't a thing yet). EWF was a large ensemble, and they played a wide variety of music in concert, with a lot of soloing. Their current album was Open Our Eyes, their fifth album and third on Columbia. It went to #1 on the Soul charts and #15 on the Billboard pop charts. They often performed on tour with white rock bands. As a teenager, I would have compared them to War, if somewhat more uptempo. I saw them (in October 1973) opening for Rod Stewart & The Faces, so this rock festival appearance was within their regular universe.

Secondly, it's important to remember that the goal of the Cal Jam booking was to make sure that every carload of friends from a High School had a band that they liked. Even if long-haired boys were the primary market, hopping into their parents' station wagons to catch Purple or Ozzy, lots of other tastes were accounted for. The Eagles were catchy, Seals & Crofts were thoughtful, and Earth, Wind & Fire was funky. Plenty of white teenagers liked EWF, or any popular soul band, so their booking wasn't some attempt to attract an African-American crowd. The idea was that if your girlfriend thought ELP was pretentious and boring--as, I assure you, many a 1974 girlfriend did--they could look forward to funking out with EWF instead.

Rare Earth had the odd distinction of being the first all-white band to have a hit on Motown Records. Rare Earth were a self-contained band from Detroit, who had been signed to Motown's fledgling rock label, also called Rare Earth (after the band). Rare Earth were great singers, and in 1969 they had a huge, memorable hit with "Get Ready," which would reach #4. In 1970, they would have another big hit with "Celebrate" which reached #7.

By 1974, Rare Earth had released six albums. There most recent album had been Ma, released on Motown back in April 1973. Produced by Norman Whitfield, it was apparently pretty good, but it didn't sell. So by the time of Cal Jam, everybody would have recognized Rare Earth and their big hits, but they wouldn't have been a big attraction. Similar to Earth, Wind & Fire, however, they would have been generally popular without being identical to some of the other bands on the bill.

Since the entire event would be broadcast later on ABC-TV, it's not surprising that a popular former LA DJ with a national profile was hired to be the MC. It is startling to realize, at this distant remove, that the DJ was Don Imus. Imus had practically invented the "Shock Jock" genre in Southern California, and by 1974 was the morning Drive Time dj on WABC 660 AM in New York City.

Remember the goal. Have an all-day rock festival with somewhat broad appeal, in order to draw 15-25 year olds from all over Southern California. More importantly, the goal was to ensure that admission was controlled, so that each member of the hopefully vast crowd would have to have paid for a ticket to get in, and that the event was orderly and under control. Ontario Motor Speedway was all but custom designed to meet each of these goals.

It almost worked.

Before we address the concert itself, we have to address the Achilles Heel of every major rock festival, which is ticket sales, parking and crowd control prior to the concert, particularly the day before. Ontario Motor Speedway may as well have been ideal, but it was still madness. The best description of the run-up to the show comes from the Facebook Cal Jam Fansite. It has lots of great posts and links, and if you've read this far I highly recommend clicking on it (you can access most of it without FB membership). For the purposes of this blog post, I have excerpted some highlights from the FB page Admin. I have left some entertaining details out, since I am focused on parking and crowd control. The description is from Allen Pamplin, then a 15-year old High School student in Northridge, CA.

Read it and smile, or weep--they don't allow this anymore, nor probably should they. You should probably put on "Burn" (the live version) and crank it up high while you read (emphasis mine):

Hello, my name is allen pamplin,

The California Jam - on April 6th, 1974, was a large concert event held at the Ontario Motor Speedway in Ontario California. It was my first professional rock and roll concert I had ever been to. I was 15 years old at this time, in ninth grade going to Nobel Junior High in Northridge California. Prior to the concert, I didn't know anything about the event, or even knew I was going until 3:00 pm Friday April 5th, 1974. That's about 19 hours before the concert started. I don't remember why I didn't know anything about the concert. I found out later that all my friends knew about the event before it took place...

I don't remember much about the drive. We drove to Ontario from San Fernando Valley in separate vehicles. My brother Karey and I drove in a Ford Country Squire, and Bill and Dave in a Van. I'm amazed we managed to stay together during the drive. We arrived at the speedway parking-lot (west end) at about 11:00 pm. I don't remember it being that difficult to park, plenty of body traffic here and there at the time. Later I understand it was impossible to park in either speedway lots because of inadequate parking-personnel. But at 11:00 pm you could still get a parking spot, even though there were thousands of cars and bodies already there. I would estimate about a quarter of the entire audience was there in the speedway parking-lots the night before. I wouldn't say we were exactly an audience at that point. We appeared to be more like a mob of lost travelers that migrated to this remote party in the middle of nowhere.The parking-lot was indeed a scene to behold, people everywhere. I've been to a lot of the San Fernando Valley parties in those days, but nothing quite compared to this. I'm in the West end parking-lot, and everything I'm seeing here is also going on at the East end of the speedway just one mile down the road on the opposite side of the speedway. Essentially, each lot is about 175 acres of dirt-grass field with a potential of about 25,000 cars. I started to walk around the parking lot and check the place out. It was a little overwhelming walking between poorly lit rows of cars, along with people in the thousands. It looked more like field-party with drugs everywhere. You could buy drugs from almost anyone there, and use it right out in the open. I can see drug exchanges going on all over the parking-lot with people partying out of cars, trucks and in backs of vans. Some vehicles had "drugs for sale" signs posted on their vehicles. Wow, just imagine the biggest street party that you have ever been to in the 70's, and multiply that by 1000. No kidding, at least a thousand.

When I reached the first bon fire... and I'm not talking about some small campfire. When I say bon fire, I mean BON FIRE. I mean this particular bon fire had at least a couple of trees in it. I became more relaxed when I joined the first circle of fifty or so people around the fire waiting for the speedway to open. Seemed like a bunch of friendly mellow people, excited and wanting to have a good time...

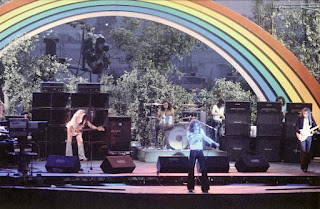

The gates opened around 1:00 am, and everyone started migrating toward the entrance. Hell, who knew were that was? It was dark and all you did was be a cow and follow the person in front of you; and god only knows what state-of-mind they're in. Somehow we were in a tunnel and into the infield of the speedway. There was no line, a guy looked at my ticket, tore it, and in I go, into this well-lit big open infield.From far away I could see the rainbow on the stage [the stage was bracketed by a neon-lighted rainbow]. That was the first thing I remember focusing on as I walked across the vast open field. I was amazed, in a dream-like state in all that space. My brother kept saying, "Come on, we got to catch up with those guys!"...

We finally caught up with them behind the mixing tower that is slightly left of the stage. Now the decision from here is to go right or left of the tower. We went left, and around in front of the mixing tower, and up next to the fence at the press enclosure. The fence had brown canvas tied to it that obscured some of the view near the stage. We stood and looked around and said, "Yeah, this looks good", and sat down. It's now about 2:30 am with the stage in front, the camera crane to the right, and the mixing tower behind us with a shitload of people all around relaxing, partying and waiting for the show to begin. This is where I held my ground for the entire concert, twenty-one hours before my next piss break.

Parking was nightmarish for many. The 42,000-car lot filled up and traffic backed up for 13 miles at times on both the 10 and 60 freeways.

The CHP closed the off-ramps nearest the speedway and directed motorists to surface streets. Frustrated fans began parking in surrounding vineyards and vacant land. Some abandoned their cars three- and four-deep along the 10 Freeway’s shoulders and walked as far as four miles, according to contemporary accounts.

Afterward, many returned to their vehicles to find they’d been either ticketed or towed. Bummer.Even from a vantage point 40 feet above the stage, the sea of humanity stretched as far as the eye could see,” David Shaw wrote in the Los Angeles Times. “With temperatures hovering near 85, bikinis, shorts and bare chests were plentiful, and the scene at times looked more like a Sunday afternoon at the beach than a rock festival.”

Bands stayed at a Holiday Inn whose marquee sign read “Welcome Western States Police Officers Assn.” to scare off fans. Band members were transported to the concert by helicopter.

Two stages were mounted on a temporary railroad track. When one stage was in use, the other was being prepped for the next band, ensuring no downtime between acts. The setup was so efficient, the first act went on 15 minutes early.

Live On Stage

Since highlights from every set were broadcast on ABC In Concert over the next few months, we have an excellent idea of what each band sounded like (see the In Concert episode list below). Still, the California Jam was different than almost every rock festival that came before it. For one thing, the show actually ran according to schedule, probably thanks to the double stage and the railroad tracks. All the lessons learned from previous mega-shows had been assimilated, and bands got on and off the stage in timely fashion. The weather co-operated, with a perfect 85 degree day and only mild smog.

There was an unexpected subplot to the timely show. Deep Purple, one of the principal attractions, had it in their contract that they would appear at twilight, just as the sun was going down. Purple was up next-to-last, with Emerson, Lake & Palmer set to close the show. Deep Purple was nominally scheduled for something like 5:00pm, with the assumption that the show would be running behind anyway. When the show actually ran on time, Deep Purple refused to come on stage since it was not twilight. They had a signed contract, after all. Still, with 200,000 or more fans waiting in the hot sun, it wasn't a great moment for a delay. At other festivals, there might have been trouble, but not in Ontario. No major trouble ensued--fortunately--and Deep Purple kicked it off when the sun went down (on the ABC In Concert segment, you can hear Purple asking "where's the sunset?" only to see that it's behind them).

Deep Purple's delay, however. meant that ELP went on late as well, and the show ran somewhat later than had been originally intended. Fellow organists Jon Lord and Keith Emerson, old pals from tiny clubs on the English R&B circuit in the mid-60s, found their bands at odds over a contractual disagreement at a gigantic racetrack with more people than had seen either band at every concert in the 60s combined.

How Many People Were There, And How Many Paid?According to Circus Magazine, there was a paid attendance of 168,000, at $10.00. I assume this information came from Pollstar, or another industry magazine. This would make California Jam the rock concert with the largest paid attendance in history up until this time, as Watkins Glen apparently only had 150,000. Casual press accounts suggest that over 200,00 were attended, while ABC In Concert said that 300,000 were there. Obviously, no one knows. Many people must have gotten it without a ticket, but was it 25,000 extra or 100,000? Review the crowd shots and decide for yourself. I have no idea how many people came late or left early. Allen Pamplin (from the FB fansite) was there from 2:30am until nearly midnight, as many must have been, but it probably wasn't everyone.

Still, the gate was at least $1.68 million, serious money for 1974. ABC In Concert was directly or indirectly providing financial support for the show, whether up front or after the fact. ABC would have either helped with production costs in return for airing the show, or else paid a fee once the episodes were aired. Either way, money would have gone to the promoters. No one died. There wasn't a riot. It was a sunny day. By and large, many of the fans had the time of their lives. Why not do it again, and soon?

August 3, 1974 Ontario Motor Speedway, Ontario, CA: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young/Beach Boys/Joe Walsh/Jesse Colin Young/The Band Shelly Finkel and Jim Koplik in Association with Bill Graham Presents "Summer Jam West" (Saturday) canceled

There were two big stadium-level acts touring in the Summer of '74. One was the Allman Brothers, and the other was the reunited Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Both of them were booked to headline different racetrack shows in August, but only one of the shows actually happened.

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young had stopped recording and performing in the middle of 1970, at the height of their popularity. They spent the next few years releasing individual solo albums with a fair amount of success, and making surprise guest appearances at each other's concerts. Ultimately, all four of the principals played a sloppy but well-received acoustic set at a Stephen Stills' Manassas concert in San Francisco (October 4, 1973 at Winterland), and the path seemed clear for a much-anticipated reunion. Nothing came easy for them, and no album was completed at the time. Nonetheless, CSNY did get together for a national tour, a massive one, headlining huge outdoor facilities, mostly football stadiums. In Southern California, however, they were booked at Ontario Motor Speedway. CSNY could probably draw an infinite number of ticket buyers, and Ontario seemed a plausible venue.

The show was promoted by Shelly Finkel and Jim Koplik in Association with Bill Graham Presents. Bill Graham was organizing the entire CSNY tour. Finkel and Koplik were based in New England, and had promoted the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen where 600,000 had come to see the Allman Brothers, the Grateful Dead and The Band. Graham had provided a sound system at the Glen, so although the promoters were fundamentally rivals this event was big enough to share the booking. A lot of money was at risk for such a huge event, a huge outlay that could lead to a huge win, so its not surprising that the risk and opportunity was shared.

Graham, Finkel and Koplik were all invading the territory of other Southern California promoters. Since Ontario Motor Speedway had rarely been used as a concert venue--only two concerts had actually been produced there--no other promoter had any exclusive contract to it. This had clearly been the strategy Graham had been planning on when he had attempted to book the Allmans and the Dead in May '73, but ticket sales (most likely) thwarted him. Here was trying again with an even bigger act, and the same team that had pulled off the Dead and the Allmans at the Glen.

Supporting CSNY was The Band, who had just completed their own legendary tour with Bob Dylan earlier in the year, along with the Beach Boys, Joe Walsh and Jesse Colin Young. Although Walsh could rock a little bit, at this time he was seen as more of a mellow Colorado dude than the hard-charging leader of the ear-splitting James Gang. The entire booking was directed towards a mellower crowd, very far from the audience of rowdy boys who had wanted to rock out to ELP, Deep Purple and Sabbath.

|

| Thanks to ace reporter David Allen of the San Bernardino Sun, we know that Richard Nunez of Pomona, CA not only has his ticket to CSNY at Ontario Motor Speedway for August 3, 1974, he's got the receipt |

The all-day Saturday event wasn't just a rumor, as tickets actually went on sale. The cost was $12.50 per, a 25% raise over the Cal Jam charge. San Bernardino Sun reporter David Allen even found someone who still has a ticket (note the mere 75-cent service charge--good times!). But the show was canceled. CSNY played a number of stadium dates around the country, but they did not play the Los Angeles area. My suspicion--unprovable--is that the somewhat mellower, older crowd (older as in "mid-20s") had heard about the madhouse at Cal Jam and thought "that's not for me." The corollary to this assertion was "my girlfriend would never put up with it." This was no small thing. Just about every rock fan in Southern California must have known someone who attended Cal Jam, and there didn't seem to be a desire to repeat it. So "Summer Jam West" never happened.

August 10 1974 Charlotte Motor Speedway, Concord, NC: Allman Brothers Band/Emerson, Lake & Palmer/B/Eagles/Foghat/Marshal Tucker Band/Ozark Mountain Daredevils/Grinderswith/PFM (Saturday) "August Jam" Kaleidoscope Productions Wolfman Jack MC (Eagles cxld)

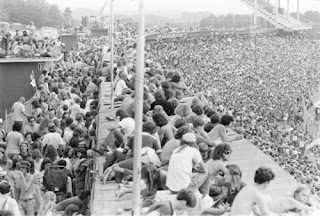

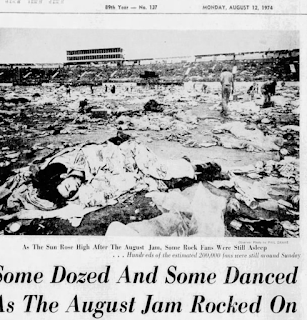

There was a sequel of sorts to Cal Jam, however. The Charlotte Motor Speedway held its only rock concert on August 10, 1974. The Allman Brothers headlined, ELP was there, and the Eagles were booked, although they canceled in the end. In Charlotte, or even in the Greater Southeast, fans would have seen Cal Jam on ABC In Concert, but most kids wouldn't have known anyone who went. In any case, with the Allmans and ELP, the crowd was much more aimed at rowdy long-haired boys, rather than the mellower fans of CSNY and The Beach Boys booked for Ontario. The August Jam happened, and something like 200,000 fans showed up. Many of them paid. Charlotte Motor Speedway is still open, and still thriving but has never held a rock concert again.

|

| A crowd shot from the grandstands at Charlotte Motor Speedway for the August Jam (August 10, 1974) |

|

| The Charlotte Observer (Monday August 12, 1974) focused on the debris-strewn infield of the Charlotte Motor Speedway after the Saturday (August 10) August Jam concert headlined by the Allman Brothers |

The August Jam had all the typical problems of rock festivals in some farmer's fields: huge traffic jams, lack of crowd control, too many gatechrashers. The coverage in the Charlotte Observer treated it like the aftermath of a natural disaster, like a hurricane. There have been no more rock concerts at Charlotte Motor Speedway. Now, part of that was a change of track ownership in January 1976 (Bruton Smith regained control and put Humpy Wheeler in charge, for those who know their NASCAR), and there was a renewed interest in racing. Still, there was no appetite for any kind of big outdoor rock event. The Allman Brothers Band were in their prime of popularity, and a huge draw in the Southeast, and it seems to have created an event that was too big to risk repeating. In that respect, it was the NASCAR replay of Watkins Glen.

|

| Anaheim Stadium, ca. 1973 |

Anaheim Stadium, 2000 Gene Autry Way, Anaheim, CA

Anaheim Stadium, home of the California Angels, had been built in 1967. It was essentially across the street from Disneyland. At first, they had resisted concerts, not least because the rock market wasn't big enough to fill a stadium. The Disney Company, in any case, would not have wanted a horde of teenagers causing a traffic jam that created a Disneyland access problem. By 1975, this had changed. Stadium concerts were common throughout the country, and Southern California wasn't going to be left behind. Anaheim Stadium was a city-owned facility, so they weren't going to pass up significant paydays that huge rock concerts would generate.

Initially, Anaheim Stadium held some concerts with less hard rocking bookings--the Beach Boys and Chicago on May 23, 1975, and The Eagles, Jackson Browne and Linda Ronstadt on September 28, 1975. By 1976, Anaheim Stadium was booking The Who (March 21), Yes and Peter Frampton (July 6, 1976) and then a slew of hard rock headliners for the balance of the summer (ZZ Top, the Winter brothers, and so on). With Anaheim Stadium as a willing home for stadium tours, there wasn't an incentive to make a stab at having a rock concert at Ontario Speedway again, however big it had been.

Nonetheless, there's no way the venue that held the highest paid attendance rock concert ever could not have an encore. On March 18, 1978, Ontario Motor Speedway hosted "California Jam II." Guess what? Cal Jam 2 had even bigger paid attendance than the first Cal Jam. I don't think it was coincidental that it was a full four years between Ontario Motor Speedway events. After 1974, the freshman in every high school and college would still have been in school the next few years, telling everyone how cool Cal Jam had been, and how they had gotten sunburned and lost the car and couldn't see the bands, and all the other things that happened at every rock festival ever. By 1978, however, those underclassmen had moved on, and so the lure of Cal Jam II would have had fewer seniors (in college or High School) offering cautionary tales.

Cal Jam 2 was promoted by perhaps the largest Southern California concert promoter at the time, Wolf & Rismiller Presents. Jim Rismiller and Stephen Wolf had been promotional partners since the 60s, eventually selling their company to Filmways, although they continued to run it. Sadly, Stephen Wolf had been killed in a home burglary in 1977, but Rissmiller kept the business thriving for many years, keeping his old friend's name on the company.

The show appeared to have a similar funding structure to Cal Jam, in that it was backed by TV and Record Company money. The entire concert was filmed for an ABC Television special, and Columbia Records released a double-lp of Cal Jam 2 highlights. Almost all of the acts were on Columbia. The only two that were not on Columbia--Foreigner and Bob Welch--were not on the double album. The three smaller acts who were not on the poster (Jean-Michel Jarre, Rubicon and Frank Marino and Mahogany Rush) were all Columbia acts, and they all had tracks on the double-lp.

|

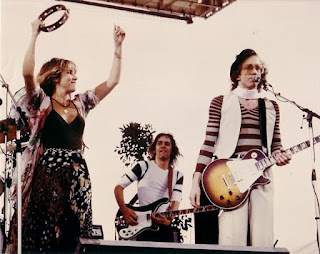

| Stevie Nicks joined Bob Welch on stage at Cal Jam 2 (Ontario Motor Speedway March 18, 1978) |

The two non-Columbia acts were critical to the concert. Foreigner (on Atlantic) had released their debut album the previous year, and had scored with two massive singles "Feels Like The First Time" (which would reach #4 on Billboard) and then "Cold As Ice" (which was released in July '77). Guitarist Bob Welch had left Fleetwood Mac in 1974, right before Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks joined to make the band huge. Yet his September 1977 Capitol album French Kiss included Buckingham, Christine McVie and Mick Fleetwood and went double platinum (helped by his remake of his old Mac tune "Sentimental Lady"). At Cal Jam 2, Welch was joined on stage by Stevie Nicks, so he bought a lot of star power to the event.

Cal Jam 2 went off reasonably well. Supposedly there were as many as 300,000 in attendance. How many paid? I have read different numbers. At least, it seems there were more paid than at the first one. Since tickets were $12.50 in advance ($17.00 at the door), the total gate would have been massive. If 200,000 tickets had been sold, than the gate was $2.5million, and that's not counting revenue from the TV special. Could there have been a Cal Jam 3? Maybe. But only if there was an Ontario Motor Speedway.

Ontario Motor Speedway, Ontario, CA: August 1970-December 1980

The Ontario Motor Speedway had been imaginatively conceived, a custom-designed motor sports facility decades ahead of its time. The racing was great throughout the 1970s. Los Angeles is Los Angeles, however, and the track never drew the crowds it had expected. In the later 1970s, auto racing's popularity had flattened somewhat, and that didn't help either. Ontario's appeal had been that it was so near to greater Los Angeles, but that it was also its downfall. The track was losing money, or perhaps barely breaking even. LA was expanding, however, so the land underneath the racetrack was more valuable than the facility itself:

By 1980, the Ontario Motor Speedway bonds were selling at approximately $0.30 on the dollar. Generally unknown and unrealized by the bond-holding public, the 800 acres (3.2 km2) of land originally purchased at an average price of $7,500 per acre, had now risen to a value of $150,000 per acre. Chevron Land Company, a division of Chevron Corporation recognized the opportunity to acquire the bonds and effectively foreclosed on the real estate. For approximately $10 million, Chevron acquired land which had a commercial real estate development value of $120 million, without regard to the historic significance or future potential of the speedway.

After just a decade, Ontario Motor Speedway closed in December, 1980. The racing was still great--at the final California 500 Indy Car race (August 31 '80), after 200 laps and 500 miles of racing, Bobby Unser (in a Penske PC9) only beat out Johnny Rutherford (Chapparal 2K) by just 8 seconds. In the final Los Angeles Times 500 at the Speedway (Nov 15 '80), Benny Parsons had just edged out Neil Bonnet, Cale Yarborough, Bobby Allison and Dale Earnhardt, all of whom were on the same lap. The great racing didn't matter--Ontario Motor Speedway was sold to developers and the track was closed. It was a sad moment in Southern California motor sport history, but the rock concert potential of the Speedway disappeared as well.

Aftermath

Riverside Raceway, the great road course that had preceded Ontario, was also sold to developers and closed in 1988. Yet, in 1995, ground had been broken for a new speedway in Fontana built on the OMS model. The California Speedway--today Auto Club Speedway--opened for racing in 1997. The track is just a few miles from the site of the Ontario Motor Speedway. Although owned and operated by NASCAR, Auto Club Speedway has been a hugely successful track, with all kinds of racing. No rock concerts, though.

Ontario now has Citizens Business Bank Arena, a concert and sports venue on a portion of the old speedway property. Two walls of the concourse are devoted to California Jam photos and text, including a 2002 article by yours truly [David Allen] blown up to cover a wall.

“My husband hitched a ride here for California Jam,” said Sue Oxarart, the arena’s marketing director. “The crowd was so large, he got up, went to the restroom, came back and never could find his friends. This was before cellphones. So you’d just find a new spot and make new friends.”

Two of the eight acts from the 1974 festival, the Eagles and Earth, Wind and Fire, have performed at the arena, as has Foreigner, one of the 1978 bands. All three made reference to the festival either onstage or backstage, Oxarart said.

A warm, sunny Spring day in Southern California. Twelve hours of music. 168,000-plus paid. The stuff dreams are made of.

The speedway was bordered on the north by 4th Avenue (then referred to as San Bernardino Avenue), on the south by Interstate 10, the west by Haven Avenue, and the east by Milliken Avenue, which still has the eastward curve needed to make room for turn 1 and turn 2 of the racetrack. Milliken Avenue is one of (maybe the only) street with curves like this in the entire city.

Contrary to those news reports about the Ontario Mills Mall being built inside the old racetrack, this is not the case. Ontario Mills Mall lies across the street, due-east of what was the racetrack, on the east side of Milliken Avenue. When the Speedway was still in existence, the future home of Ontario Mills Mall was either empty fields, or parking areas, depending on the year.

Even though virtually nothing remains of the race track, other than some of the raised-berms that made turn number 3 at the corner of 4th and Haven Avenues, The City Of Ontario has retained some of the history and heritage of the racetrack by building Ontario Motor Speedway Park a few blocks west of the racetrack site and by using auto racing inspired street names in and around the old speedway. Let’s give Ontario some credit for these street names! (Jaguar Way, Corvette Dr, etc)

The telltale remnants of turn 3 can be viewed here.

Show 37: May 10, 1974 [California Jam part 1]

Emerson Lake and Palmer - Pictures at an Exhibition

Deep Purple - Space Truckin'

Eagles - Take it Easy

Seals and Crofts-Summer Breeze

Rare Earth - I Just Want to Celebrate

Black Oak Arkansas - Hot 'n' Nasty

Earth Wind and Fire - Come On Children

Black Sabbath - Children Of The Grave

Show 38: May 24, 1974 [California Jam part 2]

Deep Purple - Smoke On the Water, Burn, Might Just Take Your Life, MistreatedShow 39: June 7, 1974 [California Jam part 3]

Black Sabbath - War Pigs, Sabra Cadabra

Rare Earth - Hey Big Brother

Emerson Lake and Palmer - Karn Evil 9 Impressions 1 and 3, Lucky Man, Still You Turn Me On, Take a PebbleShow 40: June 21, 1974 [California Jam part 4]

Black Oak Arkansas - Hot 'n' Nasty, Dixie, Mutants of the Monster

Seals and Crofts - Hummingbird, We May Never Pass This Way Again, Diamond Girl

Eagles - Witchy Woman, Peaceful Easy Feeling, Already Gone, On the Border

Earth Wind and Fire - Power, Keep Your Head to the Sky

Deep Purple's set was officially released in 1996 as California Jamming. The ELP set was released on cd in 2012.

|

| Columbia released a double-lp of California Jam 2 later in 1978. Foreigner and Bob Welch (nor Stevie Nicks) were not on the record, since they weren't Columbia acts. |

|

| NASCAR Grid ready for the green flag at Ontario Motor Speedway, probably at the 1971 race (won by AJ Foyt for the Wood Brothers) |

No comments:

Post a Comment