The Troubadour, 9081 Santa Monica Blvd, West Hollywood, CA

In the latter 60s, rock bands made their bones in the ballrooms, with the light shows and people swaying. Word would pass on the underground telegraph that Cream or Quicksilver Messenger Service or Ten Years After were great, and you would check them out the next time they came to town. There were a few rock nightclubs, but most fans weren't even 21 yet, and clubs in any case were too small to create much residual buzz, not compared to a college gym.

In the 1960s, however, there was one major exception to

this rule. The infamous Whisky-A-Go-Go club in West Hollywood (at 8901 Sunset Blvd) defied all these conventions. Name bands played

for union scale just to get heard. The Hollywood hip people, whether in

the record industry or just cool cats, heard the bands and helped to

decide who got some buzz. In August 1966, the house band at the Whisky

were some unknowns called The Doors, and they became as big as anybody.

In January, 1969, a new group built on the ashes of the old Yardbirds

played the Whisky, and within a week the word was out about Led

Zeppelin.

Hollywood proper had been part of the city of Los

Angeles since the 1930s. But West Hollywood was unincorporated, part of

the county, but not the city. It was insulated from the notorious Los

Angeles police and the machinations of the LA City Council. Thus West

Hollywood was, paradoxically, the entertainment district for Hollywood,

and had been since the 1940s. There were clubs, restaurants and jazz,

and plenty of stars came to hang out, and that was how tastes got made.

Rock and roll wasn't that different. The Whisky had opened in 1964, and

made "Go-Go" a thing. By 1966, the club had a new act every week, all

trying to catch the Hollywood buzz. Cream and Jimi Hendrix each played

there in 1967, for practically nothing, just so that people would listen. So did

numerous other ambitious groups, because rocking the Whisky was a ticket

to a big tour.

A mile East of the Whisky, however, was a former

coffee shop called The Troubadour. Proprietor Doug Weston had opened the

club in 1957, but by 1970 it had a full bar and regular performers.

Initially it presented folk acts, and in a sense it still did. Electric

instruments were standard fare by the end of the 60s, and the Troubadour

wasn't for purists. But the Whisky was for rocking out, and the

Troubadour was for reflection. As the 70s rose on the horizon,

reflection was the order of the day, and success at The Troubadour

turned out to have more impact than success at the Whisky.

|

| Linda Ronstadt had been a regular performer at the Troubadour since the mid-60s. Her album Silk Purse had been released on Capitol in April 1970 |

Troubadour Performance List, September-December 1970

The Troubadour was open seven days a week, with performers every night. The restaurant and particularly the bar were open as well, so it was a hangout for music industry types as well as musicians. Supposedly, many 70s bands, such as the Eagles, had their beginnings in the Troubadour bar. Troubadour bookings were almost always from Tuesday through Sunday. The Tuesday night show was almost always reviewed in the Thursday Los Angeles Times, giving industry and fans an idea of what was worth seeing that weekend. A good review in the Times, followed by a packed house on the weekend, could make an artist's career, as it did with Elton John in August, 1970.

Maximum capacity at the Troubadour was about 300.

Generally, there were two shows each night, and sometimes three shows on

weekend nights. Sets were relatively short, from what I can tell,

in order to turn the house over. Headliners would play about 40 minutes,

and openers nearer to 20. The Troubadour was a showcase, not a place

where performers jammed all night with their pals. I don't know whether

the Troubadour had the arrangement where if the late show was not sold

out, patrons could stick around if they would buy another drink (or some

such arrangement). For a packed James Taylor/Carole King show in

November of 1970, the Times reported that all 4000 tickets were sold

out, but I don't know if that was for 12 or 14 shows, and whether it was

an approximation, but it gives us an idea of capacity.

Monday nights were "Audition Nights." Performers were booked, but they weren't advertised in the papers. Presumably, patrons could call the club, or the bands were listed at the club itself. In some cases, record companies would arrange to have performers play Monday night at the Troubadour so they could invite a few people and check them out. I assume that when a performer did not have a full Tuesday-Sunday run, and no performer was listed (usually a Tuesday or a Sunday), "auditions" were booked on those open nights too. I think one reason to call these booking auditions was also to minimize what they were paying the performer (probably just union scale). I don't think there was an admission charge on audition night. I'm not aware of any way to retrieve who played on Audition nights (and I appear to be the first attempting to capture who played the Troubadour during this period).

At the beginning of 1970, many of the acts at the Whisky had their eyes on Las Vegas, Television Variety shows and the big hotels. Hippie acts that might have been welcome at the Fillmore, or even a college campus, weren't that common. By the end of the year, the hair had gotten longer and the stakes had gotten higher. Rock music and the record industry was turning out to be big money, and finding the next big recording artist was more important than knowing who was looking good for the Ambassador Hotel downtown or the Sands in Vegas.

In a previous post, I reviewed the performers at the Troubadour from January through April 1970. In a short time, the Troubadour went from mostly featuring performers looking to get on TV or into Las Vegas to long haired singer songwriters that are famous today. It was becoming clear that there was big money in the booming record industry, and the Troubadour was right at the center. The next post reviewed the performers at the Troubadour from May through August 1970. It also covered the opening of the ill-fated Troubadour in San Francisco.

This post will review all the performers at the Troubadour from September through December 1970. This will also include the performers at the San Francisco Troubadour, indicated here (for convenience) as "Troubadour (North)." In a distinct contrast, the West Hollywood Troubadour booked some of the most important and best-selling acts of the 1970s, while the San Francisco Troubadour folded without fanfare by Halloween.September 1-6, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco, CA: Elton John/David Ackles (Tuesday-Sunday)

The display ad above (from the August 28, 1970 Examiner) is one of the very few traces of Elton John's appearance at the San Francisco Troubadour. Following his pattern, Weston booked Elton John for a week in San Francisco right after his Los Angeles debut. Elton's performance at the Hollywood Troubadour made his career, changed his life and was a milestone in popular music.

It is telling that Elton John's similar performance in San Francisco disappeared almost without a trace. I'll save you the trouble of googling--I'm the only person to write about it. Even the first-rate Eltonography site can only allude to it vaguely. Now, let's be clear--the SF Examiner reviewed the opening night, and the reviewer (Michael Kelton) acknowledges Elton's talent, energy and songs. But he dismisses him for being "inauthentic," although he uses the term "artificial." The San Francisco ethic at the time was Jerry Garcia or Carlos Santana, crouched and squinting over their guitars, not a guy in a sequined suit jumping around. Elton John's appearance at the Hollywood Troubadour is the centerpiece of his bio-movie--his appearance at the same club in San Francisco is barely even noted in the website devoted to his history.

Music and the music industry was changing, and the center of gravity was heading south down Highway 101, from San Francisco to Los Angeles. By the end of 1970, the West Hollywood Troubadour was one of the most important venues in popular music. The San Francisco Troubadour would only last two more months, and disappear with almost no trace.

David Ackles, an American songwriter, had released his second album on Elektra in 1970, Subway To The Country. Ackles was highly regarded by British artists like Elton John, Elvis Costello and Phil Collins, but he did not become known at all until later, and he was never really popular. Ackles opened for Elton John at the Troubadour in both Hollywood (Aug 25-30) and San Francisco. Apparently Elton watched Ackles' show every night. Bernie Taupin would produce Ackles' 3rd album (American Gothic), released in 1972.

September 2-6, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Fairport Convention/David Rea (Wednesday-Sunday)

Fairport Convention, then fairly obscure, had opened at the Troubadour back in April. Five months later, they were returning as headliners. Their previous album, Liege And Leaf (released in the States on A&M in December 1969), had all but single-handedly invented English folk-rock. Songs like "Come All Ye Roving Minstrels" and "Matty Groves" were getting good FM airplay all over the country. Yet for their first American tour, Fairport had been without their most recognizable member, lead singer Sandy Denny. Of course, all that meant was that lead guitarist Richard Thompson was even more prominent. Despite the short opening sets, Fairport clearly caught the ears of the locals, since the band returned as headliners a few months later (in September), and every musician in Los Angeles apparently showed up.

In July, A&M had released Full House, yet another stunning album, despite Sandy Denny's departure. By this time, Richard Thompson and Simon Nicol were playing guitars, Dave Swarbrick had his unique electrified take on traditional fiddle, and there was a solid rhythm section with Dave Pegg (bass) and Dave Mattacks (drums). Thompson and Swarbrick handled the vocals, replacing Denny's soaring voice with gruff charm.

A&M Records had the sense to record the Fairport Convention shows on the weekend (September 4-6). Highlights were included on the album Live At The Troubadour. That album was released in 1977, during a lull in Fairport releases. Further highlights were included on a subsequent 1986 archival release House Full. The music was sensational. According to the liner notes, members of Led Zeppelin showed up for a late night jam, although apparently Led Zeppelin manager Peter Grant took possession of the tapes, never to be seen again.

More intriguingly, per the notes, Linda Ronstadt was present, and for an encore, Richard Thompson said from the stage (approximately), "we hear Linda Ronstadt is here, would she like to join us?" (since Linda was in the front row, it was hardly a secret). Linda was pushed on stage by her friends, and sheepishly told the band "I don't know any of your material." Gallantly, Richard and the band said "that's alright--we know all of yours," Linda belted out the a capella intro to "Silver Threads and Golden Needles" and the Fairports crashed in right on queue.

Take a moment to consider that Linda was then a struggling solo artist, and Fairport Convention had just lost their female vocalist. Maybe...? But it didn't happen, more's the pity.

David Rea (1946-2011) was born in Ohio. In the early 60s, Rea moved to Toronto, working as a guitarist for Gordon Lightfoot and Ian & Sylvia. Joni Mitchell and Neil Young encouraged him to write his own songs, and some of them were recorded by Ian & Sylvia. Rea became an established sideman in Toronto and elsewhere, recording with a wide variety of of artists. Rea released two albums on Capitol Records in 1969 (Maverick Child) and 1971 (By The Grace Of God), both produced by Felix Pappalardi. Pappalardi had helped produce Cream, among other bands, and played bass and produced the band Mountain.

Since Rea was produced by Pappalardi, he worked with the members of Mountain on his record. As it happened, Rea ended up co-writing a song with Mountain guitarist Leslie West, the immortal "Mississippi Queen." If you say "I don't know 'Mississippi Queen'" you are probably wrong. It was a classic rock tune if there ever was one, and it was in regular use for beer commercials well into the 21st century. When you hear drummer Corky Laing's ringing cowbell, and West's blazing guitar intro, you know what avalanche is coming. To my knowledge, "Mississippi Queen" was the only song West and Rea wrote together, and way out of Rea's normal range, but it confers immortality on its own.

In 1972, Rea would rather unexpectedly joined Fairport Convention for a few months. Fairport was in flux (in between Babbacombe Lee and Fairport Nine), and guitarist Simon Nicol had left. Roger Hill had joined as guitarist, and Rea joined as the lead guitarist. Stalwarts Dave Swarbrick on fiddle and Dave Pegg on bass remained, along with drummer Tom Farnell. Odd as this seems--it's odd--when we consider that David Rea opened for Fairport at the Troubadour in Los Angeles on September 4-6, 1970, we know at least that there was some connection.

Rea and Fairport recorded an album that was never

released, since Rea was, essentially, "too American" for the band (tagged The Manor Sessions, it was ultimately released as part of disc 4 of Come All Ye: The First Ten Years 7-disc set in 2017). Rea even toured with them a little bit in Summer '72 (I think I heard a tape from My Father's Place in Long Island), but it just wasn't a fit. Rea left later in 72, replaced by Jerry Donahue. Presumably, Rea would never have been in Fairport if he hadn't met them at the Troubadour on this weekend (Rea would go on to record the album Slewfoot for Columbia, produced by, of all people, the Grateful Dead's Bob Weir. That's another story, but I have summarized what can be known).

September 7, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco, CA: Naked Lunch (Monday)

The SF Troubadour also had an "Audition Night" on Mondays. This night was one of the few times that the booked act was actually listed in the SF Examiner. Naked Lunch was a sort of proto-Latin rock band, with horns and a conga player. Guitarist Abel Zarate would end up being a founding member of Malo. Keyboard player Lu Stephens had been in the SF group All Men Joy. Naked Lunch would not release a record during the life of the band, but ultimately an archival cd from this period was released in 2013.

The Monday night "Auditions" were often listed in the SF Examiner, but no other acts were mentioned.

September 8-13, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Rick Nelson's Stone Canyon Band/David Bevans (Tuesday-Sunday)

Rick Nelson had been a radio and television star since the 1950s, as the real-life and TV son of Ozzie and Harriet Nelson. In the early 60s, teenage Ricky liked rockabilly music, so most episodes of Ozzie And Harriet featured Ricky playing a song with his band. His band included the great James Burton on guitar, and for pop music, it was pretty rockin'. Thanks to the power of TV, the records sold massively, and songs like "Hello Mary Lou" are classics today.

By the end of the decade, with Ozzie And Harriet off the air, Rick (not Ricky) Nelson was more interested in country rock in the style of Bob Dylan's Nashville Skyline. His new album was called Rick Sings Nelson, credited to Ricky Nelson and The Stone Canyon Band. The Stone Canyon Band included pedal steel guitarist Tom Brumley, an All-Star from Buck Owens' Buckaroos. Also in the band were guitarist Allan Kemp, drummer Patrick Shanahan and bassist Peter Cetera. Rick Nelson had played the Troubadour back in May, so the fact that he was back was a positive sign.

David Bevans was an impressionist.

September 8-13, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco, CA: David Rea/Timber (Tuesday-Sunday)

David Rea headlined this week in San Francisco. Weston had a sensible plan of offering two bookings, one in each city, which was appealing to a touring band. Originally, the Gabor Szabo Sextet had been advertised for this week, but seems to have been replaced by Rea. Phil Elwood reviewed Rea positively. He also gave generally positive notes to Timber as well, describing them as a 4-piece country rock group.

September 15-20, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Nitty Gritty Dirt Band/Steve Martin (Tuesday-Sunday)

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band had been founded in 1966 in Long Beach, CA, and had released five albums by 1969. Initially somewhat successful, in a country-folk vein, they "went electric" but did not thrive. At the end of 1968, after appearing in the musical Paint Your Wagon, they temporarily broke up. Late in 1969, the band had reformulated itself. Their new album on Liberty was Uncle Charlie and His Dog Teddy. Manager Bill McEuen had renegotiated their contract, giving the group more artistic control. The band now emphasized a more pronounced country/bluegrass style, shying away from straight pop music. The band still featured Jeff Hanna as primary vocalist, Jimmie Fadden and Jimmy Ibbotson on guitars, John McEuen (Bill's brother) on banjo and various stringed instruments, and Les Thompson on bass. Most of the group sang, and between them they played a wide spread of instruments. There were some drums on the album, but I'm not sure if they had a live drummer.

The album would be fairly successful. The band would make a pop hit out of Jerry Jeff Walker's ballad "Mr. Bojangles," which would reach #9 on the Billboard pop charts. In April of 1971, they would also have a modest hit (it reached #53) with their cover of Kenny Loggins' "House At Pooh Corner" ("Winnie The Pooh/Doesn't know what to do"), although the song is now associated with Loggins And Messina.

In the Fall of 1970, The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band had been broken up for over a year, so announcing a new release at the Troubadour was a good way to help them return to the spotlight. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band would never reach the huge heights that some other Troubadour performers would, but they went on to have a solid career for the next several decades.

Comedian Steve Martin had been a High School classmate of the McEuen brothers in Orange County. Bill McEuen was his manager as well as the Dirt Band's. At one point in the late 60s, he had shared a house with the Dirt Band. Martin had been a writer for the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, but the popular, yet controversial, show had been canceled by CBS in early 1970. Martin was now establishing his career as a comedian, although he often played (pretty good) banjo as part of his act.

September 15-20, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco, CA: Rick Nelson/Leigh Price and the Hurdy Gurdy Man (Tuesday-Sunday)

Leigh Price is unknown to me.

September 22-27, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: John Sebastian/Merry Clayton (Tuesday-Sunday)

John Sebastian had been hugely successful in the 1960s as the principal songwriter and lead singer of the Lovin' Spoonful. When the band broke up, there was a possibility that he might join Stephen Stills, David Crosby and Graham Nash in their new group, but all parties agreed that he was better suited to being a solo artist, and all remained friends. Sebastian had signed with Reprise records, and he had a solo album recorded and ready as early as January 1969. For whatever record company reasons, his debut album John B Sebastian was not released until January, 1970. As if that wasn't enough, due to a disputed contract, MGM Records released the same album in the middle of 1970.

Although Sebastian was not well-served by Reprise's delay and the confusing double-release by MGM, John B Sebastian did not do badly. It reached #20 on the Billboard album charts, raising the question of how well it might have done a year earlier. There were guest appearances on the album by Crosby, Stills and Nash (and drummer Dallas Taylor), and of course they were bigger stars than ever. In person, I believe Sebastian just accompanied himself, without a band.

Merry Clayton had made her recording debut at 14, in New Orleans with Bobby Darin, back in 1962. She was well-established as a background singer with Ray Charles and others when she was called in one night to sing a part on the Rolling Stones' "Gimme Shelter." In 1970, she had released the album Gimme Shelter on Ode, including her own version of the song. Although she sang the famously soulful vocal for the Stones, on stage her material was apparently in more of a Las Vegas-cabaret vein.

September 23-October 3, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco, CA: Nitty Gritty Dirt Band/Steve Martin (Wednesday-Sunday, Tuesday-Saturday)

October 1-4, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Shelley Berman/Fanny (Thursday-Sunday)Shelly Berman (1925-2017) was the kind of successful TV and Las Vegas performer who had regularly been booked at the Troubadour. As recently as Spring 1970, such bookings were common. By year's end, "singer-songwriters" were ascendant, and a far bigger draw than someone who would play on a variety show. This was no criticism of Berman, who had made several gold albums as a comedian, starting in 1957, and had regularly appeared on variety shows and in Nevada. He also had an established career as a character actor, which would continue throughout his life (you may recall him as Larry David's aging father in Curb Your Enthusiasm, ca. 2002-09). Berman seems to have been one of the last such bookings at the Troubadour, certainly the last for 1970.

Fanny was not the first all-women rock band by any means, but they were the first to get much attention from the serious rock press. Their debut album would be released on Reprise in December 1970, produced by Richard Perry.

The anchors of Fanny were

sisters Jean and June Millington, both from the Sacramento area. The

pair had fronted a Top-40 band called Svelt, which had evolved into Wild

Honey. Both Jean (guitar) and June (bass) could really play and sing,

and female musicians (as opposed to singers) were pretty rare in the

late 60s. Of course, both were knockout-cute, too, but the music

industry was still the entertainment business. Drummer Alice De Buhr had

rounded out Wild Honey, and keyboard player Nicky Barclay was added by

Reprise.

Bill Medley had been half of the Righteous Brothers (along with Bobby Hatfield), who were among the premier purveyors of "blue-eyed soul." Their songs like "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" and "Little Latin Lupe Lu" were 60s classics. Supposedly, the Phil Spector-produced "Lovin' Feeling" is the most-played song in the history of American radio. Still, the duo broke up in 1968 when Medley went solo. Medley would have some success as a solo artist. At this point, Medley's most recent album would have been Someone Is Standing Outside on A&M. Medley and Hatfield would periodically re-form over the years, as well as continue solo careers.

Judy Mayhan wrote and sang songs and accompanied herself on piano, somewhat in the style of Laura Nyro.

|

| An ad for the SF Troubadour in the SF Good Times, Oct 9, 1970 |

October 6-11, 1970 The Troubadour (North) San Francisco, CA: Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen/Dee Higgins (Tuesday-Sunday)

Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen were

rowdy hippie honky tonkers from Ann Arbor, MI. They had relocated from Michigan to Berkeley in the Summer of 1969. In the meantime, they had developed a local following for their groundbreaking mixture of Western Swing, honky-tonk and hippie sensibilities. The Cody crew were certainly the hardest rocking band yet to play the SF Troubadour (and given its brief tenure, the hardest rocking ever).

Opener Dee Higgins was a Canadian singer.

October 14-18, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: John Phillips/Barry McGuire and The Doctor (Wednesday-Sunday)

John Phillips (1935-2001) had been the principal architect, songwriter and arranger for the hugely successful band The Mamas And The Papas. The vocal quartet was only recording from 1965 to 1968, but they had 6 Top 10 singles, four successful albums and sold 40 million records. Even today, songs like "California Dreamin'" and "Monday Monday" are instantly familiar, thanks to movie soundtracks and television commercials. Although singers Cass Elliott, Michelle Phillips and Denny Doherty were more recognizable faces, Phillips was the engine that drove the machine.

Nonetheless, The Mamas And The Papas had broken up due to various intra-group conflicts, and to some extent psychedelic rock music had passed the band by. The rise of the singer-songwriter, however, seemed custom made for Phillips' return. In January, 1970, Phillips had released his first, self-titled solo album (sometimes this album is called John, The Wolf-King of LA). The songs were excellent, and well-recorded, but Phillips didn't have the vocal abilities of his cohorts, so the album was only moderately successful. Over the years, it has been critically well-regarded.

This October show at the Troubadour was apparently Phillips first engagement as a solo performer. It may have been his only one, too, or at least one of very few. The LA Times reviewer (Fredric Milstein, October 16) called him "a stylish, sensitive soloist." The Wednesday early show had an enthusiastic but half-full house. Phillips backing band, not identified by name, included bass, keyboards and a flute player.

Barry McGuire had had big folk-rock hit with "Eve Of Destruction." It had reached #1 in late 1965, but McGuire never reached those heights again. He had a duo with "The Doctor," (Eric Hord, formerly part of the Mamas And The Papas touring ensemble) who played lead guitar.

October 13-18, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco, CA: Judy Mayhan/Dick Holler (Tuesday-Sunday)

Judy Mayhan and Dick Holler were both songwriters who accompanied themselves on piano. Phil Elwood gave them both a favorable review in the October 14 Examiner.

Per the ad above, Marin county country-rockers Clover, then signed to Fantasy, were originally booked. Dick Holler replaced them.

October 20-25, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Gordon Lightfoot/Dee Higgins (Tuesday-Sunday)

Gordon Lightfoot (b. 1938) had been a successful songwriter and singer in Canada since the early 1960s. His song "Early Morning Rain" was already a standard of sorts. In the latter 60s, many Nashville country artists had also recorded his songs. Reprise Records made a push to expand Lightfoot's audience to the States with the Sit Down Young Stranger album in April 1970. Lightfoot would have a big hit in December 1970 with the single "If You Could Read My Mind." The song reached #5 in the US (and #1 in Canada). Once again, a Troubadour booking was on the front end of a successful singer/songwriter.

October 20-25, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco: CA Jo Mama/Michael Horn (Tuesday-Sunday)

Jo Mama was an interesting band, if largely forgotten today. Jo Mama's debut album on Atlantic had been released in 1970. Their follow-up, J Is For Jump, would be released later in 1971. For the most part, the band featured East Coast transplants who had relocated from New York in the late 60s. Lead guitarist and principal songwriter Danny "Kootch" Kortchmar had been in a group called The Flying Machine with James Taylor back in Greenwich Village in the mid-60s. Korthmar and bassist Charles Larkey had moved to LA around '68. They had a group called The City with Larkey's future wife Carole King, herself a recent transplant from NYC (and recently divorced from her husband, songwriter Gerry Goffin). The City had released an album on Ode Records in 1969, but Carole King didn't really like to perform much, so the band kind of expired.

By 1970, Kortchmar and Larkey formed Jo Mama with keyboardist Ralph Shuckett (another transplant) and singer Abigail Haness (Kortchmar's girlfriend), along with drummer Joel Bishop O'Brien. I, at least, can vouch for the quality of the second album (J Is For Jump). Still, the band never really got traction.

Michael Horn is unknown to me.

John Denver (1943-1997) had worked with the Kingston Trio and others, but his solo career had begun in earnest with a 1969 solo album for RCA. His second RCA album, Take Me To Tomorrow, released May 1970, featured his own songs. His album Whose Garden Was This, released by RCA in October, was mostly cover versions. Denver would not really start to hit it big until his next album, Poems, Prayers And Promises was released in May of 1971.

It's easy to dismiss John Denver as a popular lightweight, and it's not unfair. Nonetheless, when we look over the acts who played the West Hollywood Troubadour in 1970, and particularly the last part of the year, we see some of the best selling acts of the 1970s playing a 300-seat nightclub. John Denver was another of those acts, just as big as James Taylor, Elton John, Carole King, Cat Stevens or Linda Ronstadt.

October 27-November 1, 1970 The Troubadour (North), San Francisco, CA: Aliotta Haynes/James and The Good Brothers (Tuesday-Sunday)

In the October 30 Examiner, Phil Elwood reported that the San Francisco Troubadour would close after November 1. The building had apparently cost Weston $400,000, but the crowds were too small. The Troubadour was too LA-slick for hip San Francisco, while still being too freaky for the more well-to-do types at the Fairmont and other Nob Hill hotels. The restaurant had never caught on, and there wasn't any kind of foot traffic from a local "scene." The club closed quietly, almost entirely forgotten. Now, Weston had invested a ton of money, but real estate always does well in San Francisco, so he probably didn't lose that much. In any case, the West Hollywood Troubadour continued to thrive, as singer/songwriters were becoming the biggest moneymakers in the record industry.

For the final weekend, the headliners were the folk trio Aliotta Haynes. Ted and Mitch Alliota and bassist Skip Haynes apparently sounded more or less like Crosby, Stills and Nash. Bassist Mitch Alliota had played with the Chicago band Rotary Connection, and the other two played guitars.

James And The Good Brothers were a Canadian acoustic trio who were an extended part of the Grateful Dead family. Guitarist James Ackroyd had teamed with twin brothers Brian and Bruce Good, on guitar and autoharp, respectively. All sang, and their music was in a country-folk style, but without a pronounced Southern twang. The trio had met the Grateful Dead when they played on the infamous Festival Express cross-Canadian tour. The Dead invited them to San Francisco, and the trio had come down to the Bay Area, where the Dead office helped them get gigs.

James And The Good Brothers would be signed to Columbia Records in 1971, and would record at Wally Heiders with Grateful Dead engineer Betty Cantor. Jerry Garcia and Bill Kreutzmann likely played on the initial sessions, although they were not used on the final album. Ultimately the album seems to have been re-recorded in Toronto. It would be released in late 1971. Eventually, James Ackroyd would stay in California, and the Good Brothers would return to Canada, where they had a successful musical career (along with banjo-playing younger brother Larry).

The San Francisco edition of the Troubadour closed its doors after the November 1, 1970 show, largely unmourned and mostly forgotten. The venue at 960 Bush Street would reopen in March, 1971 as The Boarding House. With some changes, it would remain open for most of the 1970s, and it was a popular if not always successful San Francisco nightclub, for both music and comedy. The Boarding House was owned and run by David Allen, who had been Weston's house manager for the Troubadour and San Francisco. The very first act to play the new Boarding House, on March 26, 1971, was James And The Good Brothers.

November 3-8, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Oliver/Nolan and The Kool Aid Chemist (Tuesday-Sunday)

William Oliver Swofford (1945-2000), who used the stage name Oliver, had an interesting career and--for a pop musician--a surprisingly different post-music career. Oliver had some popular sixties hits, such as "Good Morning Starshine" and "Jean." "Starshine" (from Hair) had reached #3 in July '69, and "Jean" (the theme song to the movie The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie) reached #2 shortly afterwards. Still, Swofford grew tired of the lightweight pop sound, and throughout the 70s performed and recorded in a more folk style, using the name Bill Swofford. By the late 1970s, he had quit music.

Unlike many former pop stars, Swofford became a successful executive in an American pharmaceutical company. A leadership award at the company is named after him. Tragically, Swofford died of cancer in 2000. In another not-typical-for-a-pop-star piece of trivia, Bill Oliver Swofford's brother John was the former Athletic Director for UNC-Chapel Hill and long-time Commissioner of the Atlantic Coast Conference.

Nolan and The Kool-Aid Chemist were some kind of funk band, per a review.

November 10-15, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: John Stewart/Aliotta Haynes (Tuesday-Sunday)

John Stewart (1939-2008) had been a member of The Kingston Trio from 1961 to 1967. The group had been very popular, but they were passed by when the likes of The Beach Boys and The Beatles came along. Stewart had gone solo, and released a variety of well-received albums, such as 1969's California Bloodlines. Although he had written a hit for The Monkees ("Daydream Believer"), Stewart was well known at this time. but not particularly successful.

Stewart's current album would have been Willard, released on Capitol in 1970. The album was produced by Peter Asher, and recorded in Hollywood and Nashville. The LA tracks included players like James Taylor, Carole King, Mike Stewart (John's brother) and Chris Darrow, and the Nashville tracks had stellar backing as well. Clearly, Capitol felt Stewart was ticketed for success in the new world of singer/songwriters. When Stewart had played the San Francisco Troubadour in August, he had used Bryan Garafolo on bass and Lloyd Barata on drums (Stewart played guitar). Stewart actually had a fairly productive career into the 21st century, but in the early 70s he did not have the success that his talent would have foretold.

November 17-22, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Doug Kershaw/Bob Gibson (Tuesday-Sunday)

Cajun fiddler Doug Kershaw had been a country musician for at least a decade. His song "Diggy Diggy Lo" had reached #14 in the country charts back in 1961. Cajun music, however, was particularly suited to the amplified style of rock music, and Kershaw's remake of "Diggy Diggy Lo" had reached #69 in 1969, not too shabby for an old country guy. Kershaw's 1970 album was Spanish Moss (on Warners), made in LA with James Burton, Red Rhodes (steel guitar), Russ Kunkel (drums) and others. His version of the bluegreass classic "Orange Blossom Special" had even been a minor hit. Kershaw had played the Troubadour in May (as well as the SF Troubadour in August).

Bob Gibson (1931-1996) had been one of the earliest and most popular performers in the Folk Revival of the late 50s and early 60s. Despite his early importance--he had introduced Joan Baez at the 1959 Newport Folk Festival, for example--musical styles had passed him by. In early 1971, he would release a self-titled album on Capitol, helmed by Byrds producer Jim Dickson. The sessions included many country-rock stalwarts like Sneaky Pete Kleinow and Chris Hillman. The album would not succeed, however, and Gibson did not release an album for several more years.

November 24-29, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA:James Taylor/Carole King (Tuesday-Sunday)

The November booking of James Taylor and Carole King at the Troubadour is perhaps the most emblematic booking at the Troubadour for 1970, and for all I know its entire existence. Here were two of the biggest singer-songwriters of the 1970s, one having just become a star and the other still on her way up, playing music that we are all familiar with now. The sound of Taylor and King was paradigmatic for Los Angeles music in the 1970s--iconic, thoughtful, reflective and hugely profitable. Even if you don't like their music, or the music that followed it, James Taylor and Carole King together at the Troubadour was a signpost of the decade.

Back in February, shortly after the release of his second album, Sweet Baby James, Taylor had played a week at the Troubadour (February 10-15, 1970). Now, 9 months later, anyone under a certain age in the United States could sing along to "Fire And Rain" or "Sweet Baby James." Doug Weston, however, always made his acts sign an option contract that they would return to the Troubadour later at a fixed price. Artists didn't like these options, but they were perfectly legal. In some cases, artists apparently just bought their way out of the options (details are scant, but it was discussed in Rolling Stone, so it wasn't a dark secret). It appears here that Taylor simply came back and played a week at the club to fulfill his option.

James Taylor was booked for six nights, but I'm not certain whether there were 12 or 14 shows (sometimes Weston booked tripleheaders on the weekend). In any case, the November 10 Times reported that Weston said 4000 tickets had sold out instantly. Thus we can figure that maximum capacity at the club was around 300 (285 or 333, depending). With those kind of sales, Taylor could have played much bigger places, but presumably he had his reasons for preferring playing the Troubadour rather than paying them out.

Opening for Taylor was his friend Carole King. King, of course, had written numerous hit songs for others in New York, with her ex-husband Gerry Goffin. After her 1968 divorce, however, King had moved to Los Angeles. She had a band called The City, which included guitarist Danny Kortchmar and her future husband Charlie Larkey on bass, and they had released an album on Ode in 1969. King, however, did not like playing live, so the band broke up. Kortchmar and Larkey had gone to found Jo Mama, while King mostly played sessions around LA. She had played on Taylor's Sweet Baby James album, among many others.

In May, 1970 Ode had released Writer, Carole King's first solo album. Just about all the songs had been co-written by King with Gerry Goffin. She was backed by James Taylor and members of Jo Mama, which was pretty much the crew on Sweet Baby James. Writer wasn't particularly a chart hit, although once its followup Tapestry became one of the best selling albums of all time, the album sold plenty. Nonetheless, all the people who had jumped on tickets for the hot James Taylor had then heard Carole King, and in retrospect she was just as big a part of 70s songwriter music as he was.

December 1-6, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Waylon Jennings/Jerry Jeff Walker (Tuesday-Sunday)

Although singer-songwriters were a central component to popular 1970s music, "Outlaw Country" was just a few years behind it. In 1970, the record industry had some reason to think that "country rock" was the next big thing, combining hippie sensibilities with country songwriting, and perhaps replacing whisky with weed. Indeed, some country rock bands did pretty well in the 70s, like the New Riders Of The Purple Sage or Pure Prairie League. The Eagles, initially, had a country rock veneer, even though that rapidly evolved.

A more potent and lasting merger of country music and the 60s would be the music coming out of Austin, TX. Genuine country musicians, with proper Nashville pedigrees, would move to Austin, grow their hair, light one up and pretty much play the same music they had been playing before. OK--maybe there was a bit more attitude, but that wasn't incompatible with older roughneck country, anyway. Two of the earliest converts to this were Waylon Jennings and Jerry Jeff Walker. They were booked together at the Troubadour in the first week of December. It was a couple of years before Outlaw Country and Austin were a big deal, but it was another sign that the Troubadour was a place to see what was coming up a few years down the road.

Waylon Jennings (1937-2002) was an established country singer, but he had roots in rock and roll. Jennings had been the bass player for Buddy Holly and The Crickets, and had graciously offered to give up his seat on the airplane to The Big Bopper, on the fateful flight on February 3, 1959 that crashed, killing Holly, the Bopper, and Ritchie Valens. Jennings had gone on to success as a Nashville singer, but he had never been happy with how his records were made. Jennings had made his 13th album, Singer Of Sad Songs, in Hollywood, and RCA had released it in November 1970. The record company refused to promote it, however, since they had wanted Jennings to record in Nashville. Jennings, never one to conform, was promoting it himself at The Troubadour. A few years later, he would relocate to Austin, find common cause with Willie Nelson, and Outlaw Country would become a real thing.

Jerry Jeff Walker had a more complicated story, but it was no less significant for that. Jerry Jeff had been born Ronald Clyde Crosby in Oneonta, NY. He had been a Greenwich Village folkie, then had gone psychedelic with the band Circus Maximus. In 1968, he had written the song "Mr Bojangles" (according to former accompanist David Bromberg, Jerry Jeff met the song's protagonist in a New Orleans drunk tank, where he was "doing research"). The song had recently been a hit for The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band (see September 15-20, above), so there was interest in Walker. Jerry Jeff would move to Austin within a few years. While he never became as big a star as Waylon or Willie, he was an important marker for the merger of country music and rock sensibilities that characterized the Austin scene in the 70s. At this time, his current album was Bein' Free, on Atco, produced by Tom Dowd.

December 8-13, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Cat Stevens/Seatrain (Tuesday-Sunday)

Cat Stevens (b. Steven Giorgiou 1948) had had some success in the UK in the 60s, but he fell ill and his career had been stalled. He recovered, however, and had released Mona Bone Jakon in April 1970 on Island (and A&M in the States). Stevens prior work had been fairly orchestrated pop, but his new producer Paul Samwell-Smith paired Stevens with fellow guitarist Alun Davies, for a more intimate sound. The album wasn't huge, but it had attracted some attention. Island/A&M released his new album, Tea For The Tillerman, in November. This one would be huge, the first of many big hits. The Tillerman album would reach #8 on Billboard, and the hit single "Wild World" would reach #5. Once again, the Troubadour was on the front end of a huge success.

Seatrain had been formed from the ashes of the

Blues Project in 1968. For complicated reasons, the Blues Project had

reformed in San Francisco, and then changed their name to Sea Train.

After a 1968 debut on A&M, Seatrain reconstituted itself (and

changed its spelling) and ended up recording for Capitol. The new band

was mainly based in Cambridge, MA, but they seemed to winter in the Bay

Area. At this time, Seatrain had Peter Rowan on guitar and vocals, Richard Greene as lead soloist on electric violin,

Lloyd Baskin on keyboards and vocals, Andy Kulberg on bass and Roy

Blumenfield on drums. Their first album on Capitol (entitled Seatrain) had been released in 1970, although I am not precisely sure what month it was actually released.

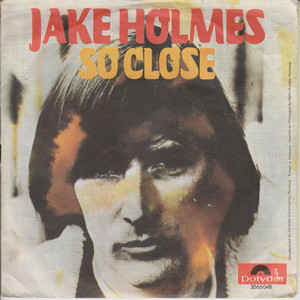

December 15-20, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Jake Holmes/Brewer and Shipley (Tuesday-Sunday)

Jake Holmes is hardly a major figure, but most Americans of a certain era have heard his songs, though not likely him. At the time of this booking, Holmes had recently released So Close, So Very Far To Go. It had been recorded in Nashville, and recently released on Polydor. The single "So Close" was apparently in the Top 20, at least in LA. Holmes was well-reviewed by Michael Sherman in the Times, who mentioned that he was accompanied by guitarist Teddy Irwin.

But that's not why you likely have heard Jake Holmes' songs. Back when Holmes had released his first album, The Above-Ground Sound of Jake Holmes, released on Tower in 1967, Holmes had toured around a little bit. On August 25, 1967 Holmes had opened for the Yardbirds at the Village Theater in Greenwich Village (later better known as the Fillmore East). A year later, Jimmy Page and The Yardbirds were doing a song called "I'm Confused," which seemed to pretty much be Holmes song "Dazed And Confused," from his album. By 1969, the first Led Zeppelin album had been released, with the song "Dazed And Confused," very similar but with writing credits assigned to Led Zeppelin.

Holmes ultimately sued for copyright infringement, and the case was settled out of court. A 2010 Led Zeppelin cd release assigned credits to "Dazed And Confused" as written by Zeppelin, but "inspired by Jake Holmes," presumably related to the settlement. But, you might say, I'm no Zeppelin fan, I don't know how the song goes, so I don't know the music of Jake Holmes.

After his recording career fizzled somewhat, Holmes wrote commercial jingles. His most famous commercial theme was the US Army recruiting song "Be All You Can Be." Jake Holmes second most famous jingle? "Be A Pepper," for Dr Pepper ("I'm a Pepper/You're A Pepper/Wouldn't you like to be a Pepper too?"). All I can say is, those three songs would that would make some medley.

Opening act Brewer And Shipley were a folk duo from the Midwest. Tom Shipley and Mike Brewer were based in Kansas City, but they recorded in San Francisco. They had just released their album Tarkio on Kama Sutra, recorded in San Francisco with producer Nick Gravenites. It was a great album that holds up well, but the first track was the catchy "One Toke Over The Line," which would be released as a single in March of 1971. It would reach #10, but it has remained prominent on oldies stations ever since.

December 22-24, 26-27, 1970 The Troubadour, West Hollywood, CA: Eric Burdon and War/Edwards-Hand (Tuesday-Thursday, Saturday-Sunday)

Eric Burdon, a powerful singer and a true character, had numerous lives in the Pop firmament. Burdon had come to prominence in the mid-60s as the lead singer for The Animals, bringing a dose of heavy blues to the British Invasion. When psychedelia hit, Burdon remade his band as the psychedelic Eric Burdon and The Animals, touring constantly and scoring with hits like "San Francsican Nights" and "Sky Pilot." Burdon and the Animals were perhaps the only British Invasion band to directly make the transition to the Fillmores, and he and his band had relocated to Los Angeles by 1968.

When the psychedelic Animals melted down, Burdon had remained in LA. After some intermittent performances (and a brief stint at USC Film School, apparently), Burdon hooked up with a local band called War. War played funky jazz, mostly focused on a groove, rather than virtuosity. Burdon's name helped them get bookings, and they gave Burdon a chance to update his sound. When Burdon played with them, he just improvised along, rather than singing his old Animals hits. A few raw audience tapes from 1970 suggest that it actually sounded pretty good--Burdon had a great voice and a good sense of drama, so he didn't overwhelm the band.

By late 1970, Eric Burdon and War were pretty successful. The album Eric Burdon Declares War had been released by MGM in April 1970. Surprisingly, the album generated a hit single "Spill The Wine," which had peaked at #3. Today, the single is pretty embarrassing. If you listen to Burdon in the context of a live show, it actually fits in, but stripped out to a single it's pompous. Still, it was a hit. In December, Eric Burdon and War released the shamefully named Black-Man's Burdon. There was no hit. Burdon would separate himself from War, and they would go on to have a pretty successful run in the early 1970s.

LA Times reviewer Susan Reilly (Dec 25 1970) described Edwards-Hand as featuring Roger Hands and Rod Edwards as singer-songwriters, backed by a trio (plus Rod Edwards on keyboards). The band had released an album on GRT, with Beatles producer George Martin at the helm.

Linda Ronstadt would be a huge star in a few years, but at this time she was a regular booking at the Troubadour. This, too, added to the ultimate status of the club---people would say they saw Linda back in the day at some club, rather than at the Sports Arena.

At this time, Ronstadt would have been supporting her second solo album, Silk Purse, which had been released on Capitol on April. She had played the club back in June (June 23-July 5). Ronstadt had been part of the Stone Poneys, with Bobby Kimmel and Kenny Edwards. The trio had released three albums in 1967 and '68, and had even scored a modest hit with the Michael Nesmith song "Different Drum," which reached #13 in 1967. The Stone Poneys had come from Tucson in 1965, and had played the Hoot Night at the Troubadour many times. Ronstadt had received offers as a solo singer, but she had refused to abandon her bandmates. Finally, after a Troubadour hoot performance in 1966, the Stone Poneys had been signed as a group.

Ronstadt would not release a new album until 1972, so in her case, the Troubadour bookings would keep the wheels turning for her.

No comments:

Post a Comment